“It was an experience of mourning, grief, celebration, commemoration, and memory.”

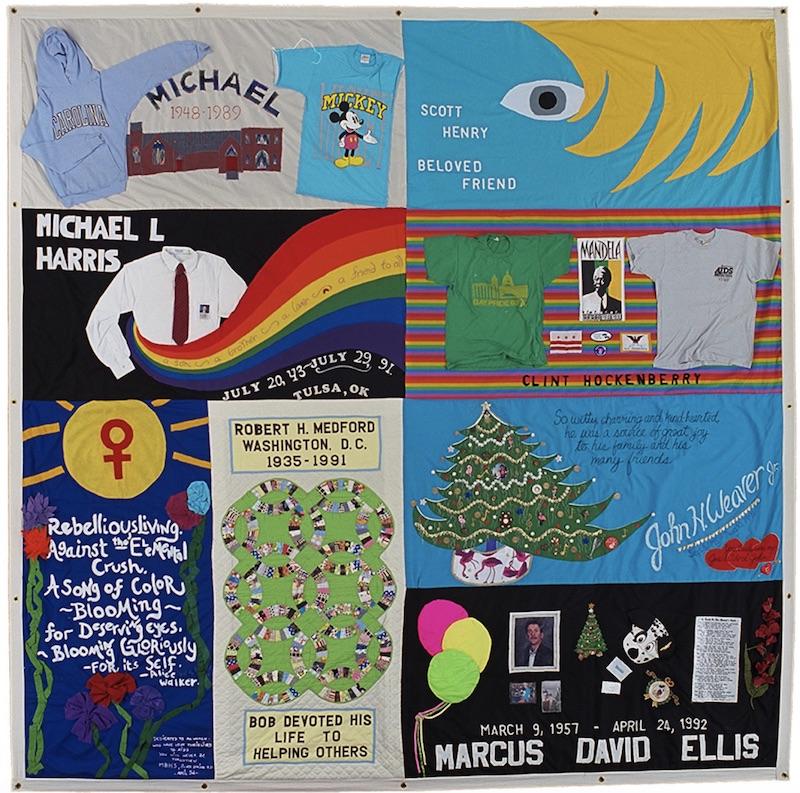

The AIDS Memorial Quilt forms an extraordinary mosaic of human grief and resolve. The collection of more than 48,000 hand-stitched panels, begun in a San Francisco backyard in 1987, reveals the human face of a public-health epidemic once shrouded in fear and misinformation. Individually, the 3-foot-by-6-foot quilt panels offer tender, intimate images of lives taken by AIDS. Together, they reveal the vast sweep of the disease and the mobilization that it spurred.

The quilt grew into a banner for the AIDS movement in the United States, mobilizing activists, seizing the government’s attention, and unleashing billions of dollars in funding for medical research. Laid out on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., for the first time in 1987, it became a public symbol for the fight for gay rights and AIDS research, helping bend the curve of AIDS deaths, which peaked in the U.S. in 1995. Richard Kurin, former director of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, calls it "probably the greatest piece of folk art ever made."

Today the quilt sits in a warehouse in Atlanta. Weighing 54 tons, it is too large to display on the National Mall or almost anywhere. The foundation that manages it has faced funding troubles and disagreements over how to steward its legacy. As AIDS deaths in the U.S. have declined, the quilt’s impact has faded too. The quilt and the movement it represents risk becoming forgotten, according to Anne Balsamo, dean of the School of New Media Studies at The New School, who delivered a Solomon Katz Distinguished Lecture at the University of Washington on March 4.

The threat of “cultural amnesia” drove Balsamo to help to build a digital version of the quilt. She has worked with collaborators at Microsoft Research, the University of Iowa, the University of Southern California, and elsewhere to bring several iterations of the quilt to life online. The digital quilt offers a multi-level experience similar to the original: Zoom out, and you get a sense of the unimaginable size of the AIDS epidemic. Zoom in, and you get a sense of the vulnerability of each life affected by the disease. The digital version is not bound by constraints of weight, fragility, or storage challenges, and—crucially—it is accessible to anyone with an internet connection.

That may help preserve the quilt’s power as a memorial and a tool for learning and activism, Balsamo says.

“As a digital designer, you don’t get many opportunities to see something that moves a viewer so profoundly,” she said.

Designing an “experience of public intimacy,” her team used digital-display tables to let viewers explore the quilt in public spaces. Watching viewers search for the quilts of loved ones was “an incredibly emotional experience,” she said. “It was an experience of mourning, grief, celebration, commemoration, and memory.”

Balsamo spoke of the fear surrounding AIDS in the 1980s, when doctors hadn’t even agreed what to name the disease and false rumors about how it spread flew rampant. In that fog of misinformation, the quilt played a role in humanizing people who had the disease. That need remains, Balsamo said. (In 2010, 15,000 people with an AIDS diagnosis died, and 50,000 were infected, according to the Centers for Disease Control.)

Balsamo spoke of cultivating a “technological imagination” to drive innovation forward: “This is the quality of mind that enables people to think with technology to transform what is known into what is possible.”

Her lecture, “Designing Culture: The Technological Imagination at Work in the Creation of Cultural Heritage,” explored how innovation is a distinctly cultural and social act, not just a technological one. She described her career moving among academia, large research ventures, and startups. In 1998, Balsamo left a tenured faculty position at Georgia Institute of Technology to join a research team at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) that created experimental reading devices. After the dot-com bust, she co-founded Onomy Labs, a Silicon Valley “cultural design” firm. At the University of Southern California and The New School, her teaching and writing have continued to explore the intersection of technology, feminism, and culture. The AIDS Quilt project typifies the collaborative nature of her career.

The quilt also highlights questions that come with forays into new media. As the NAMES Project Foundation, which manages the original quilt, struggled with uncertainty about its own future, the digital project raised new questions: Would it sap support for preserving the physical quilt? Would it diminish the communal experience of viewing the quilt in public into a private act of loading a web page? Would it lose the visceral sense of the quilt’s material nature—so crucial to its impact?

The digital quilt is not a replacement but a companion, Balsamo said. She explored questions about the digital project but did not offer simple answers, instead suggesting that such concerns are important in recognizing the cultural and social dimensions of innovation.

“Are we propagating the preference of the virtual over the physical? The digital over the material? And isn’t that a slippery slope in terms of the erasure of important cultural work and cultural memory?” she said. “That’s a very significant and serious criticism.”

She also described limitations of the digital project. It relies on photos taken over a span of 25 years, varying greatly in resolution. The photos portray blocks of eight, not individual, quilt panels. They lack meta-data to make them searchable by names. The photo collection is incomplete. And the future of their preservation is no more certain than the original quilt’s. Balsamo noted that the experimental reading machines she developed at Xerox-PARC, once the cutting-edge of computer design, are now rusting in crates in Palo Alto, a testament to the ephemeral nature of all things, even high-technology.

One criticism of the AIDS quilt is that it is overly identified with gay white men, at the expense of other victims of AIDS. A 2006 Los Angeles Times story, “The Quilt Fades to Obscurity,” reported that only 260 blocks commemorated black AIDS victims at the time, even though blacks represent nearly half of new infections. As a future project, Balsamo hopes to create “tours” of the quilt, leading viewers through an exploration of veterans, Latinos, children, and other groups affected by the disease.

In the lecture Q-and-A-session, a social-work student spoke from experience about the quilt’s shifting cultural status: “In 1985 I was a teenager,” she said. “That period of time was very impactful on me. I remember the first display of the quilt. And, in all honesty, I did kind of forget about it. What plans do you have, either now or in the future to increase the societal awareness about it? To show that it’s not just a gay thing—it’s a people thing?”

“That gets at the heart of my next project,” Balsamo responded. “It works on the notion that this is a living memorial, not a cemetery. Our focus will be on creating a narrative interface to the quilt. There are thousands of stories stitched into the quilt that we want to access.”