“Why is text necessarily the best way to convey knowledge about, say, dance? It’s in fact really difficult to translate bodily experience into text. If you want a job, you still need to write a dissertation. A lot of us struggle with that.”

In 1981, the anthropologist Renato Rosaldo saw his field research become a communal event in the worst possible way. Within days of moving to the Filipino province of Ifugao, his wife, the anthropologist Shelly Rosaldo, slipped on a mountain trail and fell 65 feet to her death, leaving behind Renato and their two young sons. The following days were a fog of hasty arrangements and surreal encounters. Thirty-three years later, Rosaldo wrote The Day of Shelly’s Death (2014), a collection of poems recounting the death and its aftermath from the perspectives of villagers, nuns, taxi drivers, a pharmacist, and a morgue worker. In ‘The Soldier,’ Rosaldo writes from the perspective of the soldier who, sent to investigate the death, sees the stunned father:

Here’s the man I was sent to find …

He’s pale, trembling, trudging,

With him two sons, a little boy and a baby.

In him I see

The same

Ashen face

Knotted shoulders

Automaton walk

My father had

The day my mother died.

In departing from traditional academic prose, Rosaldo found a form for evoking the emotional contours of a tragedy both personal and communal. In an accompanying essay, “Notes on Poetry and Ethnography,” he makes the case for poetry as a rigorous form of cultural inquiry.

“Poetic exploration resembles ethnographic inquiry in that insight emerges from specifics more than from generalizations,” he writes. “I strive for accuracy and engage in forms of inquiry where I am surprised by the unexpected.”

The book inspired one of Rosaldo’s former students, Sasha Su-Ling Welland, a University of Washington Associate Professor of Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies. She too had been questioning the limits of scholarly writing in conveying the breadth of cultural experience. After studying with Rosaldo at Stanford University, Welland earned a PhD in anthropology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, writing a dissertation on gender and globalization in Beijing’s contemporary art world. Her first book, A Thousand Miles of Dreams: The Journeys of Two Chinese Sisters (2006), blended memoir, genealogy, literary criticism, and theoretical reflection to describe the roles of her grandmother and great-aunt in the early women’s movement in China.

At the UW, she has gathered a cluster of scholars at every career stage to imagine how ethnography can reach beyond traditional methods and encompass broad forms of expression. In winter 2016, she hosted Rosaldo, filmmaker Lucien Castaing-Taylor, and ethnic and sound studies scholar Roshanak Kheshti through a speaker series, Ethnographic Aesthetics: Image, Sound, Word, supported by the Simpson Center for the Humanities. In spring 2016, she taught a new experimental ethnography course in which 13 undergraduate and graduate students showcased their fieldwork through diverse media forms. Their work included a photo essay, a crowd-sourced video, a digital archive, and a video sculpture installation. Their projects were united by a sense that scholarship should reflect the aesthetic richness of the worlds it represents.

“Why is text necessarily the best way to convey knowledge about, say, dance?” said Welland. “It’s in fact really difficult to translate bodily experience into text.”

She laments that for young scholars, most academic departments still measure success by traditional outputs such as peer-reviewed articles in scholarly journals.

“If you want a job, you still need to write a dissertation,” she said. “A lot of us struggle with that. There are all these critiques about representation, but you really can’t do something new until you get your job by performing in the traditional mode.”

For her, such critiques date back to her undergraduate studies at Stanford in the 1980s, when the campus was in the throes of the canon wars over diversity and representation in the freshman Western Culture course.

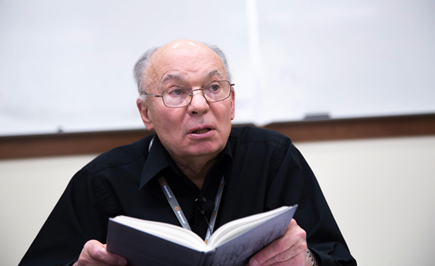

Experimental Ethnography course.

“It was a wonderful intellectual experience, but fraught with all these questions about why we started with the Bible and read almost entirely white men, with Maxine Hong-Kingston and Toni Morrison tacked on at the end,” Welland said.

“I’d been thinking about these questions before I realized it. I grew up mixed-race in a black-and-white landscape in St. Louis. The kinds of writers I was interested in reading were largely not included in the curriculum.”

As she sought faculty support for designing a custom major around literature, art, and gender and ethnic studies, Rosaldo was one of the few faculty interested in working with her. “He was the reason I became an anthropologist,” she said.

By then, Rosaldo had made his own mark in anthropology. His earlier fieldwork, in the late 1960s and early 70s, studied headhunting among the Ilongot—a Filipino tribe in which young males beheaded members of rival tribes to earn the red hornbill earrings that marked them as grown men. Drawing on classical ethnographic theory, Rosaldo sought to explain the underlying logic of the rite. That explanation eluded him.

University of Washington.

In 1981, at his wife’s death, he found himself overwhelmed by rage. “How could she abandon me? How could she have been so stupid as to fall? … I sobbed, but rage blocked my tears,” he wrote. Ilongot men had frequently told him that they killed out of rage born of grief, yet until then he could not understand them at an intuitive, visceral level. In a landmark essay in 1984, “Grief and a Headhunter’s Rage,” he explains how he came to understand the emotional force of death:

If you ask an older Ilongot man of Northern Luzon, Philippines, why he cuts off human heads, he says that rage, born of grief, impels him to kill his fellow human beings. He claims he needs a place “to carry his anger” … To him, grief, rage, and headhunting go together in a self-evident manner. Either you understand or you don’t. And, in fact, for the longest time I simply did not.

Rosaldo goes on to explain how his own rage let him understand the turmoil of young Ilongot men. He also defends his decision to insert himself into his scholarly writing. That choice acknowledges that researchers can never be fully dispassionate about their subjects. They’re better off examining their biases and social positioning than pretending they don’t exist. This amounts to a critique of the colonial notion of the “objective” ethnographer going off to study “primitive” cultures through the light of scientific reason.

The work of Welland and her students embodies this critique. It also demonstrates how ethnography, born as a “salvage field” to study dying cultures before they vanished, can shed light on emerging cultures.

courtesy Anqi Peng

Anqi Peng, a graduating Interdisciplinary Visual Arts major, created a series of short films about the lives of Chinese students at the UW. The series, ChinaTongue, follows students as they shop and cook traditional comfort foods from home, like Shaanxi lamb soup with hand-torn bread. The act of cooking opens up conversations as students discuss how often they call their parents and how they choose their majors.

One student took engineering classes to please his parents before switching to art, a choice he struggled to explain to family friends at home. “I felt pretty awkward,” he said. “Their understanding of art is very different from ours. For the sake of my parents’ ‘face’ I could not tell them I study art. They think it means one is not good at studying.”

The exchange captures particular challenges of Chinese students at American schools in the 2010s. It also captures something timeless about the experiences of young people leaving home for education or opportunity. Peng embedded the video in a sculpture installation in Odegaard Library, where viewers sat at a table set for dining. They found headphones resting in a rice bowl and peered through a transparent plate to watch a screen below. Peng sat across the table from viewers and joined them in conversation about food and culture.

“I wanted to give viewers an insider’s perspective to Chinese international students’ life,” she said. “Without the analysis and argument in my thesis, I want viewers to make sense by themselves.”

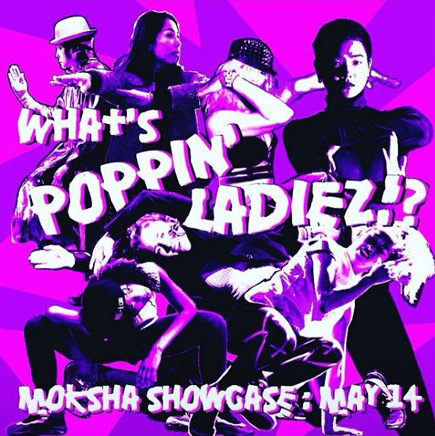

Angel Langley, a graduating dance major, created a film by stitching together crowdsourced video from a dance competition—which she also organized. After recognizing that women were poorly represented in the world of popping, a form of street dancing, she applied for a Mary Gates Leadership Scholarship to organize WHAT'S POPPIN' LADIEZ?!, a competition and celebration that brought dancers from Europe, Japan, and across the US. Although she had access to professional footage, Langley used cell-phone clips taken by participants, reflecting the way female poppers use YouTube, Instagram, and S napchat to connect. It also let her catch fun informal scenes of dancers joking, cooking, and living together.

napchat to connect. It also let her catch fun informal scenes of dancers joking, cooking, and living together.

“Rather than having a pristine and framed image … viewers witness a more intimate account,” Langley said.

Those projects take inspiration from Lucian Castaing-Taylor, director of the Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard University, whom Welland hosted in February 2016. His films avoid the narration and establishing camera shots of traditional documentaries in favor of intense, close-up recordings of manual labor that are unexpectedly demanding to watch.

In Sweetgrass (2009), as co-director with Ilisa Barbash, he tracks modern-day shepherds in Montana. In Leviathan (2012), which he screened at the UW, he follows commercial fishermen off the coast of New Bedford, Massachusetts. Much of the film is simply waves heaving in a black sea, rain pouring off faceless parkas, and gloved hands knifing open their catch. The long, unchanging shots mimic the repetitive nature of the work. The audio track does as much work as the visuals, offering a barrage of sloshing water and churning machinery.

In this way, he shows how sensory media can render emotional (or affective) experience, said Welland. He pushes against the expectation that an ethnographer’s primary task is explaining. Instead, he focuses on portraying culture in visual and auditory form.

“Interpretation doesn’t have to be so heavy-handed,” Welland said. “The sensory nature of his work is asking whether ‘textualizing’ everything is necessary.”

Welland hopes to make the experimental studio course a recurring offering. She has supported boundary-breaking work in other ways as well, serving as a faculty advisor for the outward-looking Certificate in Public Scholarship, experimenting with digital forms as a Digital Humanities Summer Fellow at the Simpson Center, and co-organizing the 2012 conference New Geographies of Feminist Art.

In her writing, Welland continues that spirit of examining the social role of art. Her forthcoming book, Experimental Beijing: Gender and Globalization in Chinese Contemporary Art (Duke University Press) tracks the shift in official attitudes toward experimental art in Beijing in the run-up to the 2008 Olympics. She charts how post-1989 censorship gave way to a market-driven mobilization of art’s ability to confer global prestige. Drawing on artists, officials, urban planners, and art professionals, Welland offers a window into reform-era China.

The title Monumental Ephemeral compares the monumental scale of public works with the precarious nature of independent art in a capitalist economy. In a beautiful description of the book, she contrasts “new monuments to China’s global future” that dominated Official Beijing while, in the work of independent artists, “other visions of being in the world glimmered at their powerful edges.”

“Like monumentality, ephemerality also memorializes, not the victor, but his shadow histories, their radical potential and their precarity,” she writes.

The work that she supports as teacher, scholar, curator, and collaborator shares that radical potential. It offers new visions, glimmering at the edges of power.