“We are not asking for an apology. We just want it to stop.” - Yvonne Swan

“The taking of Native children was not just for assimilation, but to take the land. When you break that family tie, you also break the Nation and discontinue those relationships to land.” - Nick Estes

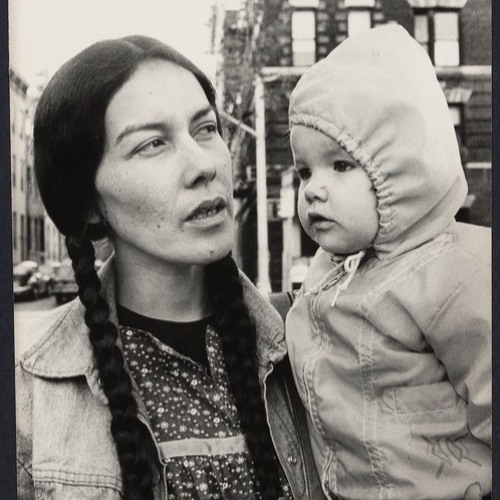

On May 6, the Simpson Center was graced with the presence and wisdom of Native American activist and citizen of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Indian Reservation Yvonne Wanrow (now Yvonne Swan) and University of New Mexico Assistant Professor of American Studies Nick Estes (Lower Brule Sioux Tribe). The sunny afternoon marked just one day since the national recognition of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Trans and Two-Spirit peoples (MMIWG2S) on May 5. As graduate students, faculty, staff, and invited guests gathered around, the Simpson Center’s meeting room grew to capacity resulting in calls for additional chairs to be brought in.

Once everyone found a seat, Swan began by introducing herself and her relatives, and acknowledged her ancestors who shaped her path. Swan described her journey to understand her culture, language, ancestors, history, and lifeways in order to remind the audience that so much of that knowledge has been erased and continues to be actively suppressed, criminalized, and held hostage by settler colonialism, which violently disregards the relationship between Indigenous bodies and the land. For Swan, her story demonstrates the historical and structural violence that Indigenous peoples have been subject to since the dawn of settler colonialism, particularly in terms of how Indigenous families have been systematically torn apart in an effort to seize land.

In 1972, Swan was arrested and charged with murder after shooting a known child molester who had tried to rape her son. In exchange for defending her child, Swan was systematically targeted with the entire weight of the U.S. justice system. From claiming that Swan had “taken the law into her own hands” to portraying her as a “hysterical woman,” prosecutors employed a number of racist and sexist tropes in order to secure a conviction of second-degree murder and first-degree assault. But Swan didn’t stop fighting. Her case, to the surprise of many, went all the way to the Washington State Supreme Court, which decided that Swan had acted in self-defense and ordered that her case be retried.

The State of Washington v. Wanrow (1977) not only recognized the legal challenges of women to effectively defend themselves and their children against male violence, but it also inspired and rallied a generation of Indigenous gender resistance movements including the Women of All Red Nations (WARN) and the American Indian Movement (AIM). In particular, her victory paved the way for international feminist and Indigenous solidarity that would foster the seeds of resistance to settler colonial violence in all of its forms, including gender violence, environmental degradation, and land dispossession. AIM was not only crucial to the legal defense of Swan, but also for facilitating the mandate to foster the health of Indigenous women, restoring and securing treaty rights, and combating the commercialization of Indigenous cultures. Similarly, WARN forged crucial global alliances that advanced legal procedures at the United Nations for the purpose of securing legal pathways to Indigenous self-determination. Though international legal progress has run at a “snail’s pace,” particularly at the UN, Swan insists that this work is vital. In fact, Swan reminded the attendees that she’s actively recruiting and seeking individuals for those who wish to continue the work, particularly with regard to the forced sterilization of Native women.

When Swan finished telling her story, Nick Estes responded by situating her legal case and the MMIWG2S movement within the broader history and processes of Indigenous elimination, particularly in relation to the kidnapping of Native children, who were placed in Indian Schools and/or with white families.

“The taking of Native children was not just for assimilation, but to take the land. When you break that family tie, you also break the Nation, and discontinue away relationships to that land,” Estes said. This process was no accident. In fact, it was created and sustained through a series of legal acts by the United States, including the institutionalization of the Doctrine of Discovery in Johnson v. M’Intosh (1823), as well as the Dawes Allotment Act (1887), which was particularly instrumental in facilitating the dispossession of Indigenous lands through imposed privatization and forced leasing, particularly of those owned by the Lakota and Dakota nations, among many others.

In particular, Indian child removal through the boarding school system was used as a key tool to eliminate Indigenous knowledge and steal land. Swan’s own experience speaks to the many people who were forced to assimilate through these de facto concentration camps, as well as to the many Indigenous women who were sterilized by the state against their will. Estes described this painful era as essential to the founding of AIM. AIM, he said, formed in 1968 to address three key issues: 1) police violence against Indigenous peoples, 2) treaty rights, and 3) Indian child removal. Indeed, the struggles that continue into the contemporary moment with MMIWG2S speak to the continued structural and institutionalized violence of the state to account for or respond to the staggering rates of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, trans and two-Spirit peoples.

In closing, Swan and Estes discussed the relationship between gender violence and resource extraction. Estes reminded the audience that when WARN organized against gender violence and Indian removal, they were also actively addressing uranium mining, coal mining, and oil drilling on Indigenous lands. Today, the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and Keystone XL, among many other pipelines, continue to foster new modes of criminalization and political imprisonment on behalf of the settler state. Estes remarked that Swan had been a political prisoner because she resisted settler violence in much the same way as today’s water protectors. Nevertheless, Indigenous women’s resistance continues. From the UN, where Swan says “it’s difficult doing human rights work when you’re not even considered human,” to the front lines at Standing Rock, the work and struggle continue. Despite the many challenges, Swan talks about the future of her activism with energy and hope. As she said in conclusion, “we are not asking for an apology. We just want it to stop.”