“The past cannot be erased. But it does need to be addressed."

Of all the accomplishments in James Gregory’s career as a historian, one discovery demonstrates his drive to bring scholarship out of the academy and into the grit of the real world.

In 2005, Gregory and his students revealed a disturbing set of housing covenants forbidding blacks, Asians, and Jews from living in many Seattle neighborhoods. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled such laws illegal in 1948, but they remained in the bylaws of homeowners associations, showing up in property deeds as an ugly symbol of the city’s ongoing struggle with racial segregation. Gregory and his students published a database of the covenants as part of the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, an expansive set of websites presenting regional history to the public.

The revelation of the housing covenants led to Seattle Times articles and an editorial calling for a state law to help neighborhoods repeal them. Within the year, the Washington state Legislature passed a law enabling neighborhoods to remove discriminatory language in the covenants.

“The past cannot be erased. But it does need to be addressed,” Gregory, a University of Washington Professor of History, wrote of the neighborhood legacy.

Gregory’s leadership prompted the Walter Chapin Simpson Center for the Humanities to award him the inaugural Barclay Simpson Prize for Scholarship in Public. The award, named for the philanthropist who endowed the Simpson Center in honor of his father, recognizes UW scholars who practice humanities scholarship as a public good.

“I cannot imagine anyone more deserving,” Lynn M. Thomas, Chair and Giovanni and Amne Costigan Endowed Professor of History, said in support of Gregory. “Jim has demonstrated to colleagues at the University of Washington and very far beyond how digital history and archival projects that are rooted in original research—often conducted by students—can engage broad publics and prompt political change.”

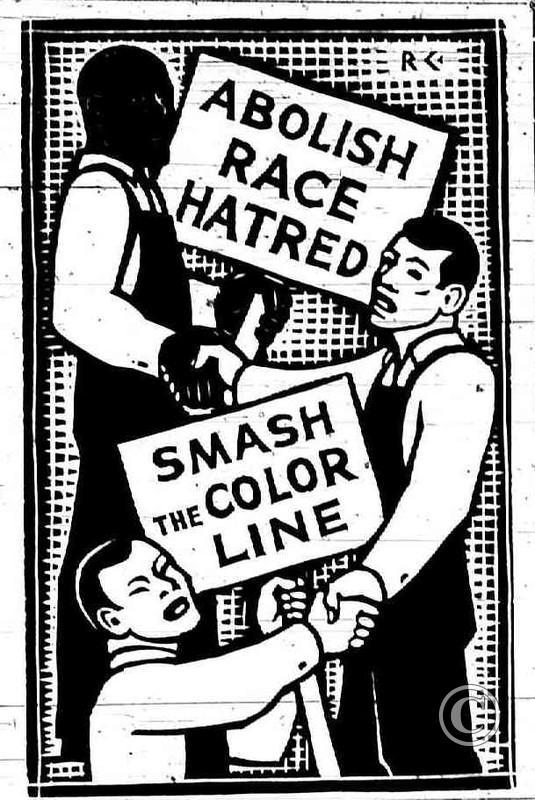

Gregory directs the Civil Rights and Labor History Project, but the project is larger than what any one scholar can accomplish. It includes eleven websites, built by UW undergraduate and graduate students under Gregory’s supervision, that publish research on an array of interconnected topics: the labor history of the Northwest, unions and communism, antiwar activism, the Seattle General Strike, farmworkers, waterfront workers, the Black Panther party, the Chicano movement, and others. The sites use text, photographs, videos, oral histories, databases, and media compilations, offering a bridge between UW scholars and the public. They have reached nearly five million page views, many from K-12 teachers developing lesson plans. Toni Morrison reportedly used the project in research for her novel Home, about a Korean War veteran who spends time in a Seattle hospital.

Gregory’s crucial contribution, says Thomas, was rallying the help of dozens of students and community partners while maintaining rigorous academic standards.

“Much of the project’s success stems from Jim’s knack for motivating skilled collaborators,” Thomas said. “If it’s true that just about anyone can put something up on the web, Jim has demonstrated the web’s potential as a resource for high-quality research and writing in the digital realm.”

Bringing a Radical Past to Light

Gregory’s academic career began with a BA from the University of California, Santa Barbara in 1975 and a PhD from the University of California, Berkeley in 1983. His first book, American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California (Oxford University Press, 1989), won the Ray Allen Billington Prize from the Organization of American Historians and the Annual Book Award from the Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association. His second book, The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (University of North Carolina Press, 2005), won the Philip Taft Labor History Book Prize.

In 2008, to help preserve the record of Washington state’s rich labor history, Gregory worked with unions, the King County Labor Council, the State Labor Council, and donors to raise hundreds of thousands of dollars to create the Labor Archives of Washington, a University Libraries special collection.

Gregory has organized dozens of panels and events, such as the 2012 “Unemployed Nation Hearings” that brought together activists, politicians, scholars, workers, and the unemployed. That event was successful enough to inspire the Washington state Legislature to hold official hearings on the issue a few months later.

Gregory is a frequent media commentator on labor issues, discussing how current living-wage campaigns are injecting new life into the labor movement. Earlier this month he appeared on a panel with Seattle’s Socialist City Council member, Kshama Sawant, to discuss how the campaigns achieved victory. He is advising the SeaTac-Seattle Minimum Wage History Project, an upcoming Simpson Center project cataloging the history of wage campaigns led by Michael McCann, Professor of Political Science and Gordon Hirabayashi Professor for Citizenship.

In the Winter 2015 issue of Dissent magazine, Gregory describes how Seattle’s robust labor history still shapes city politics, tempering (for now) the influence of new high-tech wealth. “Boomtown Seattle is also a progressive city, with loud echoes of a more radical past,” he says.

Public Outrage and Public Trust

Gregory has embraced the possibilities of digital humanities for bringing scholarship to new audiences, according to Kathleen Woodward, Director of the Simpson Center and Lockwood Professor in the Humanities. This summer, he will create a digital archive of visualizations and data sets mapping American social movements through the Simpson Center’s Digital Humanities Commons.

”Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History is a rich digital archive that has transformed the way we think about what constitutes research at the Simpson Center,” said Woodward. “It is also an archive of feelings, public feelings—including outrage at social injustice and strong ties of trust that emerged in the very process of research.

Barclay Simpson was a Bay Area industrialist who took over his father’s tiny window-screen company and built it into Simpson Manufacturing, a publicly traded building supplies company. In 1997, he and his wife, Sharon Simpson, endowed UW’s humanities center in tribute to his father, Walter Chapin Simpson. The Simpson Center announced the Barclay Simpson Prize for Scholarship in Public, which carries a $10,000 award, shortly after his passing in November 2014.

“Barclay Simpson believed strongly in the fundamental contributions the humanities can and should make to the public good,” said Woodward. “In Jim’s inspiring work we see the fulfillment of an obligation and promise of the public research university: to create spaces where multiple voices can be heard and untold histories can be disclosed, and to create knowledge that strengthens public life.”

Gregory will receive the award at a reception on June 9.