Part of the work of Anthropocene humanists may be showing when tidy administrative solutions obscure the truth.

On a dewy morning in June, a group of University of Washington students and faculty boarded a pair of minivans and traveled three-and-a-half hours into the center of the Anthropocene.

At least that’s one way to describe the Hanford Site in central Washington, the weapons production complex that fueled most of the US nuclear arsenal. Others would pinpoint the dawn of the Anthropocene—the geologic era of human influence—at the birthplace of the steam engine in 1784, or the site of England’s first textile mills and coke furnaces, where industrial-scale pollutants first poured into the atmosphere. However, a working group within the International Union of Geological Sciences has suggested that radioactivity released by the first atomic test bomb may provide the clearest stratigraphic “trace” to mark the change from one geological epoch to another. That bomb carried Hanford fuel when it fell on Alamogordo, New Mexico, in 1945. That would make Hanford, as much as anywhere, the era’s ignoble birthplace.

A 580-square-mile expanse of arid shrub-steppe, Hanford hides its radioactive heart beneath stunning desert beauty. Coyotes, elk, and eagles traverse the land. Low-slung mountains glow red in the sunlight. The mighty Columbia River courses through the site, its last unbroken stretch between dams. Yet Hanford is home to one of the largest weapons-production efforts in history, enough to destroy the earth many times over. It produced the fuel for the bomb dropped on Nagasaki in 1945 and continued for another 44 years as the nation’s largest Cold War weapons plant, producing some 60 percent of the plutonium in its arsenal.

This toxic legacy lies mostly out of sight to visitors, in restricted areas where workers still labor to manage the contamination. Rolling tumbleweeds offer just the right desert vibe—until you learn that they carry radioactivity from the site into the wider world. So too the fruit flies that made international headlines in 1998 for carrying contamination to the nearby city of Richland. As fly-fishers cast into the Columbia’s gleaming surface, contaminated groundwater leaches into its banks, flowing toward the Pacific.

The very concept of cleanup is a wishful fiction, since nuclear waste can never be erased, only stored in lined pits and buried train cars. The US Department of Energy’s remediation project, marked by emergency-cover alerts and contentious worker’s compensation disputes, is the largest such effort in the Western Hemisphere. Among its many challenges are 56 million gallons of high-level waste stored in leaking tanks and burial trenches, including plutonium that will take an estimated 240,000 years to decay.

Such figures tend to numb the mind, presenting a scale that overwhelms the mammalian brain. In this sense, Hanford is a useful test case for the age of climate change, which seems to paralyze human response precisely through its scale and scope. The UW group—the Anthropocene crossdisciplinary research cluster supported by the Simpson Center for the Humanities—came to think about how our work as teachers, students, writers, and scholars intersects with this problem.

How does the study of art, language, culture, and history connect with issues on the scale that Hanford presents? How should literary studies engage climate change? What can art offer to such problems? We took a tour led by the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, a 2014 creation of the National Park Service that groups Hanford together with two other key sites of the World War II nuclear project—Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Traveling with literary scholars turned out to be a great way to visit Hanford, because they could help me see how narratives were framed, edited, shaped, and hidden by official accounts. And on the Park Service tour, the most conspicuous stories were the ones that were missing.

‘Truly a Marvel of Engineering’

Our tour began in a temporary visitor’s center on the edge of the site. A video showed a montage of World War II scenes, including Hitler at a rally and American planes over the Pacific, but no mention of Nagasaki. It focused on the massive mobilization of the secretive Manhattan Project, which brought 51,000 workers to Hanford beginning in 1943, forming an instant city in the desert, with very few workers told what they were building. The scale is honestly impressive. In case you aren’t impressed, the Park Service can tell you that the site had eight mess halls, which served 30,000 doughnuts and 120 tons of potatoes each day. Workers and their families consumed 700 cases of Coke daily and 6,500 fried eggs on Sunday mornings. Thanksgiving required 12,000 turkeys and 12 tons of ham. (There are still more “fun facts” on the Hanford website.)

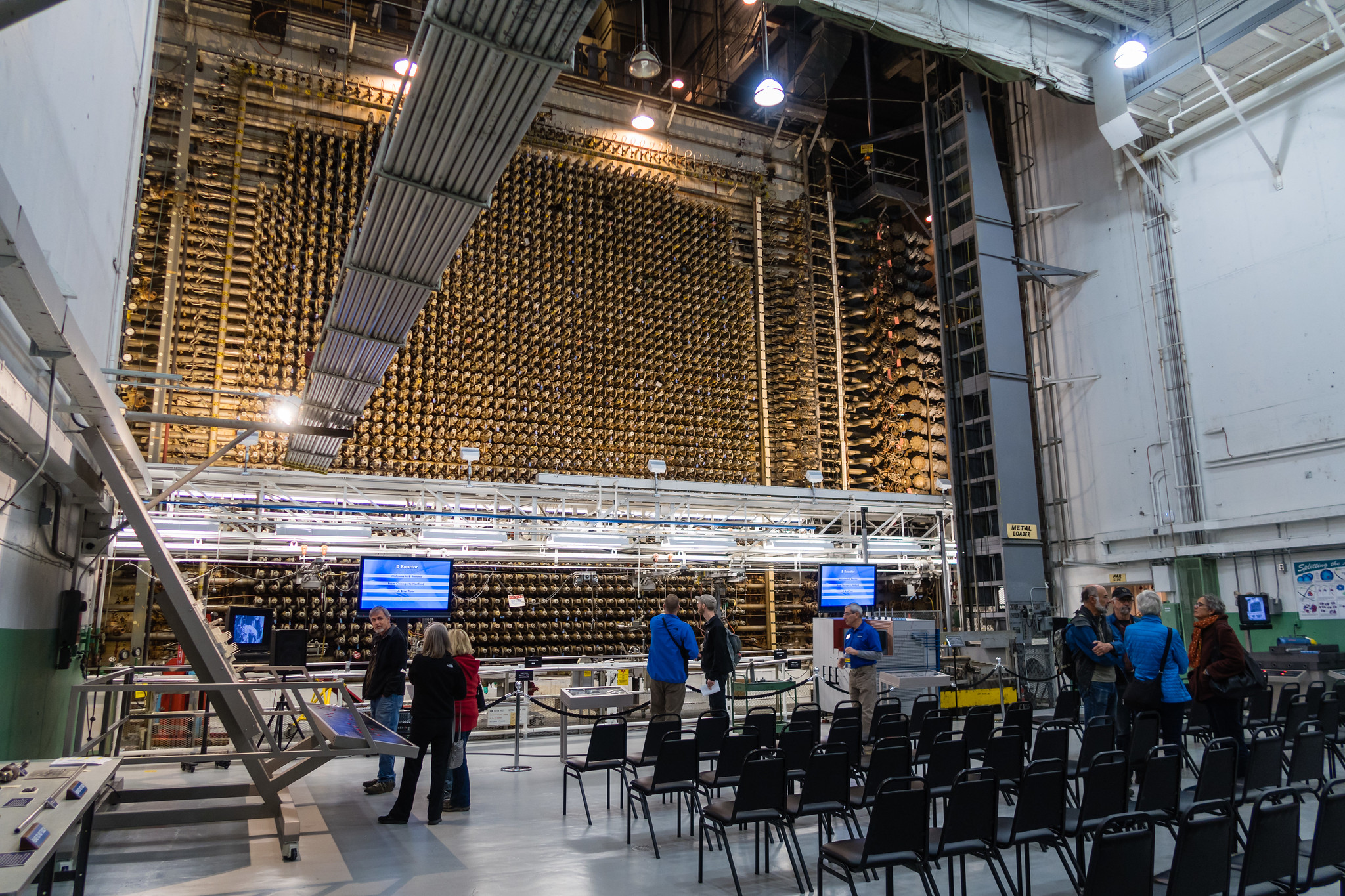

We rode a bus to the B Reactor, a gray cinder-block structure that houses the world’s first full-scale plutonium reactor. The site was chosen for its remote location and ample supply of hydro-electricity and cooling water. Our guide, an affable retired Hanford engineer, told us about the farmers who were evicted with 30 day’s notice in 1943, along with a brief mention of the Native Americans who lived there earlier.

Inside, we approached the reactor core, a massive conglomeration of rods, tubes, dials, and steel framework. Another guide gave a thorough explanation of the enrichment process, through which uranium rods were irradiated, yielding a dime-sized button of plutonium for every two tons of fuel. The substance was then recovered by dissolving the fuel rods in acid and isolating the plutonium at another facility on site.

“Truly a marvel of engineering,” she said.

It was becoming clear that this was the official line. There was still no mention of Nagasaki, or the Marshall Islands, where Hanford fuel was also detonated in test bombs, or any of the actual uses of the material produced here. I remembered a line from the visitor’s center video calling the Manhattan Project a “testament to the human spirit”—perhaps a more revealing line than intended.

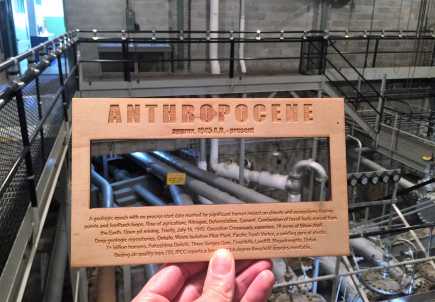

Then, surprisingly, we were set free to roam, invited to explore the reactor (retired since 1968). We wandered from room to room reading historical displays and taking pictures. Michael Swaine, Assistant Professor of Art, took photos of faint notes penciled on the concrete walls—workers scoring some game during long night shifts? He helped me notice the retro beauty of the analog display dials. Jesse Oak Taylor, Associate Professor of English and one of the research group’s co-organizers, took photos through a small wooden frame created by the artistic group Smudge Studio. The frame, called an Anthropocene Viewer, is designed to help us notice evidence of a new era hiding in plain sight.

In the control room, our guide from the bus told us how the culture of safety prevented Chernobyl-type disasters.

“I just love this place,” he said.

It was a strange tour. It’s not that nuclear engineering or a massive collective effort are boring. They aren’t. But they were being used to obscure so many other stories involving Hanford—its indigenous people, its impact on the people of Nagasaki, the racial integration and segregation among its workers, the politics of cleanup, and the continuing dilemma of Cold War nuclear stockpiles.

Even the park’s naming after the Manhattan Project limits it to a few years of the place’s history, since the Manhattan Project ended in 1946. Hanford continued producing weapons material for 43 more years, supplying fuel for most of the more than 60,000 weapons in the US nuclear arsenal. The Manhattan Project designation underscored the point of the little wooden viewfinder: the framing around a story can be as revealing as the picture itself.

Unmaking the Bomb

Anthropocene Viewer, courtesy Jesse Oak Taylor. (2017)

The Park Service does not talk about the cleanup, according to its agreement with the Department of Energy. (The Park Service did not respond to questions about this.) Guides can answer cleanup questions from visitors, but it is not part of the official narrative, according to Shannon Cram, a geographer and Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences at UW Bothell. Cram is working on an ethnographic book about “Unmaking the Bomb”— a task that receives considerably less attention than the making of the bomb. She also serves on the Hanford Advisory Board, a group of neighbors, tribal members, government officials, and others concerned with the cleanup. She says the work requires a willful suspension of disbelief: Board members know that Hanford’s waste will long outlast the regulations designed to contain it, yet they do the best they can to protect the site’s neighbors, current and future.

“Our conversations are so strange,” she said. “All of us know that full cleanup is not possible. But when we come to the table as an advisory board, we act like it is and focus on what we can do.”

Draping administrative language around the problem—and the Energy Department and other agencies produce reams and reams of language—mirrors the attempt to confine the waste itself, Cram says. The task is complicated by a fluid planet and its ever-moving creatures.

In a 2015 journal article, Cram details the Energy Department’s use of a standardized human to calculate permissible exposure limits for a post-cleanup landscape. The future Hanford resident “Jane,” in Cram’s imaginative retelling (the Energy Department calls her Subsistence Farmer), maintains a steady breath rate of 0.63 cubic meters per hour each day. After work, she takes a bath for precisely 34.8 minutes, making sure to submerge 18,000 square centimeters of her skin. She sleeps for exactly 8.0 hours each night, weighs 70.0 kilograms each day of her adult life, and consumes an identical weekly diet of permissible levels of meat, eggs, fish, fruits, and vegetables.

Cram goes on to reveal the ways that not all humans are Jane. For one, Jane is a man. Scientists from the International Commission on Radiation Protection created a male statistical model, then realized that women’s bodies respond differently to pollution than men’s. Rather than overhaul the model, they added breasts and a uterus to it. Their model is informed by studies of Japanese hibakusha—survivors of nuclear attacks—field research limited by accessibility, taboos against speaking about nuclear contamination, and the fact that, as the first nuclear scientists knew, the full impacts of radiation would not be seen for multiple generations. Nonetheless, models like Jane live on as administrative fictions, used wherever nuclear contamination needs to be measured.

“Jane” also obscures the fact that not all humans live and breathe the same. This has critical implications for three Native American tribes given use rights to Hanford’s lands in perpetuity through treaty in 1855. The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR), for example, argue that models like Jane fail to account for exposure pathways specific to tribal people—things like gathering traditional foods and medicines, eating more salmon than the Energy Department’s standardized human, and using water from the Columbia River in sweat lodge ceremonies. Likewise, the Yakama Nation has compelled federal administrators to consider that the amount of air a human body inhales per day (20 cubic meters, according to the Energy Department), is not a fixed rate transferable from person to person, from culture to culture.

Planetary Boundaries

Cram subtitles her book “Nuclear Cleanup and the Politics of Impossibility” to suggest that some realities are impossible for bureaucracies solve (even if we had the political will and sufficient funding for them, which we don’t).

We might think of our geological era as defined by greenhouse gases, nuclear radiation, and other environmental factors. The bureaucratization of the world may be another of its distinctive features. Part of the work of Anthropocene humanists may be showing when tidy administrative solutions obscure the truth.

The Anthropocene designation has not been officially adopted by international geologists, who have working groups upon subcommittees upon task forces deliberating over the term and its proper starting point. But it has become useful for showing how human development is crashing into multiple “planetary boundaries” (a concept put forth in a 2009 Nature article), of which climate change is only one. Others include massive species loss, ocean acidification, chemical pollution, and land-use change.

The term has also become a useful concept for a breadth of disciplines rethinking how their work should change in light of a new era. Since launching in fall 2016, the UW Anthropocene research group has convened lively discussions over this topic, hosting visiting scholars and artists. A number of its conversations have been catalyzed by Amitav Ghosh’s book The Great Derangement (2016), which explores why supposedly serious literature struggles to engage with climate change.

The Nation’s Storytellers

The National Park Service styles itself as “The Nation’s Storyteller,” promoting its role educating and interpreting history for Americans and global visitors. While the stories tend to be positive, it has done admirable work presenting shameful histories at sites like US internment camps. Lydia Heberling, a doctoral student in English studying American Indian literatures and arts, told me how parks such as Yellowstone and Olympic have improved how they include the histories of indigenous people.

Yet Hanford poses particular challenges. The Manhattan Project historical park, created by Congress three years ago and funded with a scant $680,000 budget across three sites, is still developing its full message. Hal Bernton of The Seattle Times wrote an excellent story in August detailing the Park Service’s struggle with how to tell the story. He traveled to Nagasaki to interview bomb survivors about the impact. He described the renovated Los Alamos History Museum in New Mexico, funded with a mix of private and county dollars, which includes a “reflections space” with artifacts from Japan and quotes from survivors.

Bernton also retold the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s effort in the 1990s to combine an exhibit of the Enola Gay, the aircraft that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, with a look at the on-the-ground toll. The US Senate intervened to forbid any mention of the bomb’s impact as “revisionist and offensive to many World War II veterans.”

Former Representative Doc Hastings, a Washington Republican who advocated for the park’s creation, said the focus should be on patriotism. “Of course there are consequences to war, but the emphasis ought to be on the American ingenuity that developed the bomb,” he told the Times.

Even the stories of the Nagasaki explosion victims may be easier to render than the harm visited upon Hanford workers, Marshall Islanders, and others damaged by the slow accumulation of exposure over time, as Cram points out. She borrows an enormously helpful term from scholar Rob Nixon—“slow violence”—to suggest that much harm in the Anthropocene era is gradual and accumulative, toxins seeping into your bloodstream like wastewater into a riverbed.

Investigative Poetry

It’s not my role here to referee debates over whether the nuclear attacks were justified, whether they prevented the need for a bloody land invasion of Japan, whether they were worse than Nazi and Japanese atrocities or, for that matter, the Allied fire-bombing of Tokyo and German cities, or military violence today. Historians have debated those questions, as they should. So should conscientious citizens. If the Park Service is going to call itself the nation’s storyteller, these questions are relevant to the nation's stories.

A healthy culture will never have a singular, authoritative storyteller. It needs many storytellers, official and unofficial, from the top, bottom, and all levels of historical struggles. (I’m aware that I’m telling my perspective from a comfortable campus office and a position of relative privilege.)

The poet Kathleen Flenniken, the daughter of a Hanford worker and a onetime Hanford engineer and hydrologist, shows how longtime residents can reveal what others can’t. Her book Plume (2012), which won the Washington State Book Award, captures the texture of growing up in suburban Richland while parents performed dangerous and often-unspoken cleanup work. The book, a poetry cycle that also functions as investigative documentary, captures the devastation of cancer that tore through Hanford workers and their families.

“He never said no I won’t / to work nobody else would do,” she writes in “Dinner with Carolyn,” about the death of a friend’s father.“ He could have known his grandchildren.”

Traveling with UW scholars and artists helped me see that negotiating who gets to tell stories matters deeply. Heberling spoke about how tribal communities carry long-term knowledge that even well-intentioned bureaucrats lack. Jason Groves, Assistant Professor of Germanics and a co-organizer of the group, compared the site with how Germans handle remembrance of their own past atrocities. Jesse Oak Taylor considered how Cram’s technocratic “Jane” fits alongside other attempts to imagine “posthuman” future beings.

We barely even touched other questions: What to think about the undeniable pride that Richland—home of the Richland High School Bombers—takes in its role in ending World War II? How do complex concepts like “posthuman beings” translate into undergraduate classes? How do we get poetry like Flenniken’s into the hands of politicians?

For a scholar in the Anthropocene, perhaps the proper scope of study is not a single discipline but everything: geologic strata, fruit flies, bureaucratic tedium, gut-wrenching poetry, and all the tangled connections they contain. The same holds for any attentive student of the world. A radioactive site in the desert is only one place to start.

Related

- Anthropocene Research Cluster webpage

- Climate-fiction scholar Stephanie LeMenager (University of Oregon) visits the group for a lecture on January 18, 2018.

- Anthropocene Reading: Literary History in Geologic Times, a new book co-edited by Jesse Oak Taylor and Tobias Meneley (University of California, Davis, and a 2016 visiting speaker of the Anthropocene cluster)

- A review of Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement in The Seattle Review of Books by Jonathan Hiskes.

- Kathleen Flenniken has several good video and audio recordings from Plume on her website.