"We all live within states," he said. "We cannot escape that. Nevertheless, states like the US or Japan are just a historical and illusionary framework. Living in that frame, Homo sapiens have developed their individual abilities to connect to nature, and one of the channels connecting people to nature is art."

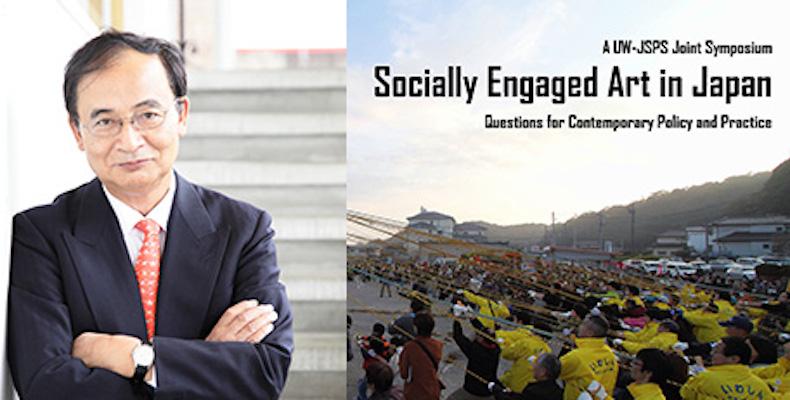

Artists, curators, and scholars were gathered from around the world, but the most talked-about guest was the one who wasn’t there. Two days before the symposium Socially Engaged Art in Japan at the University of Washington in November 2015, organizers announced that the celebrated curator Kitagawa Fram had been denied entry to the US, allegedly due to his role protesting a military base expansion in the 1960s, nearly 50 years ago.

The event went on anyway: Kitagawa delivered a video greeting from Japan and organizer Justin Jesty (Asian Languages & Literature) read his keynote address to a crowded audience at the Henry Art Gallery. The fear that seems to have motivated Homeland Security officials, Kitagawa said in his video, “runs precisely counter to art’s infinite faith in human possibility.”

"We all live within states," he said. "We cannot escape that. Nevertheless, states like the US or Japan are just a historical and illusionary framework. Living in that frame, Homo sapiens have developed their individual abilities to connect to nature, and one of the channels connecting people to nature is art."

Kitagawa has traveled to the US before, and he provided documents showing he was never charged with a crime. We may never know, Jesty said, whether the denial arose from “bureaucratic stupidity” or because protests have arisen again over US military expansion in Japan.

The conflict underscores the fraught relationship between art and politics, a key idea the conference examined. Another key focus: the power of art to adapt to changing social conditions, something the organizers mirrored in adapting to the travel ban.

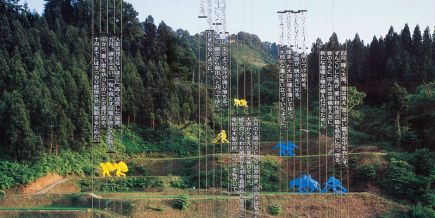

The irony beneath it all is the relative gentleness of Kitagawa’s work. For nearly 20 years, he has led the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, a festival in a remote mountainous district that brings visitors to discover art placed in villages, forests, rice fields, and abandoned schools and businesses. The Niigata region has long supplied soldiers and workers for Japan’s urban growth, and it experiences an extreme version of Japan’s aging and shrinking population. The triennale has in many cases literally turned the lights back on in shuttered buildings. Once-wary residents work with the artists, volunteering to co-create stunning outdoor works, tend landscapes, collect tickets, and guide visitors.

The event demonstrates a back-to-nature character, encouraging creators and viewers alike to slow down, explore the world around them, and enjoy the process of creating and discovering art as much as the finished product.

Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale. Photo: ANZAI

The Beauty of Uselessness

Echigo-Tsumari exemplifies a global surge in work crossing boundaries between art and activism. At the conference, sponsored by the UW Simpson Center for the Humanities, speakers described this work as a counterbalance to the increasingly commodified global art market. Where consumer-oriented art emphasizes the talent of a lone artist, socially engaged art prizes collaboration.

Kumakura Sumiko, Professor in the Tokyo University of the Arts Department of Musical Creativity & the Environment, presented a fascinating case study that bears this out. Sun Self Hotel is a twice-yearly project in which a modest apartment complex in suburban Tokyo becomes an elaborate “hotel” run by volunteers from the neighborhood, ages 4 to 80.

Guests must apply to stay months in advance, and when they arrive, they receive personal tours, finding rooms decorated with handmade curtains, lampshades, and bedsheets. They receive solar-powered batteries to charge, although the rooms invariably run out of electricity. Guests are constantly accompanied by volunteers, and they are asked to play card games invented by neighborhood children—essentially becoming entertainment for the youngest “staff.”

Guests find themselves both flattered and flustered by the lavish attention, Kumakura said. They eat meals prepared by stay-at-home-mom chefs, planned over months. At night, everyone gathers in the courtyard for the unveiling of the night sun, which elicits wild celebration seemingly out of proportion for a simple globe with LED lights inside.

The DIY hotel functions as a parody of commercialism, poking gentle fun at the customer-service ethos of the corporate world and giving roles to small children and seniors not considered “useful” by the market economy. The project also highlights the essential “purposelessness” and “irrationality” of works of beauty, in Kumakura’s words, which is the source of their “captivating magnetism.”

Courtesy of Toride Art Project.

Identity beyond Growth

Others at the conference grappled with art’s ability to intervene in social problems. Japan does not have the warfare, famine, or pervasive dire poverty that roil other parts of the world, Jesty noted. Instead, it struggles with loneliness, a feeling of emptiness, high suicide rates, and a sense of malaise or stagnation.

“These are problems that modern society has never dealt with very well,” he said.

They also can be fertile ground for neo-nationalism, he added.

There is a pressing need to find a sense of connection and shared identity that does not rely on perpetual economic growth, he said, since that may be impossible for a population decreasing in number. Kawashima Nobuko, Professor of Economics at Doshisha University, argued that art can nurture such connections, but it needs stronger public support. Others spoke of Japan as a lens for understanding broader global trends, including UW’s Sasha Welland (Anthropology), a scholar of Chinese art, and Adrian Favell (Sociology & Social Theory, University of Leeds, UK), who praised the inefficiency of art in cultures that reward speed and competition.

“Culture and the arts have been considered a personal hobby with little significance to society at large,” Kawashima said, “Much of this government indifference stems from a national preoccupation with economic development.”

“We Must Not Look Away”

The symposium’s second keynote provided a sharp-toothed counterpoint to the gentle, playful style of Kitagawa and Sun Self Hotel. Sharon Daniel, an American artist and Professor of Film & Digital Media at University of California, Santa Cruz, places justice issues of racism and mass incarceration front and center in the interactive digital designs she presented.

Her volunteer work with drug users in Oakland, California, led her into state prisons, where she interviewed female inmates and presented their stories in Public Secrets, a Flash-based portal published in Vectors (a leading-edge digital journal). When viewers explore Public Secrets, clicking through cells of audio and text, they hear the stories of people the state has tried to silence.

“I haven’t seen my children since I got busted” says one inmate, Misty Rojo. “… You didn’t deny me. You denied my children.”

Daniel met Beverly Henry, a woman who spent 42 of her 65 years imprisoned for nonviolent drug offenses, Daniel said. Her video Undoing Time/PLEDGE shows Henry holding a large American flag—the same flag she sewed for 65 cents an hour inside a “flag factory” at Central California Women's Facility. As an African American, a woman, a lesbian, and an HIV-positive drug user, Henry says she was a target for the worst biases of the US penal system. In the video, she tears apart the flag, saying “this is what happens to the lives of the have-nots in America. They get shredded.”

In the interactive displays, which require viewers to choose their paths through blocks displayed algorithmically, information design becomes a form of argument, Daniel said. The user’s path becomes a form of inquiry.

Even the act of zooming in on a screen becomes charged with meaning.

“We must get closer,” said Daniel. “We must not look away.”

The symposium Socially Engaged Art in Japan was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Simpson Center for the Humanities, the Japan Faculty in Humanities and Arts, the UW Japan Program, the Japan Foundation Center for Global Partnership, the Japan-US Friendship Commission, the Department of Asian Languages and Literature, Urban@UW, and the School of Art + Art History + Design.